In 1789, Antoine Lavoisier published a list of 33 chemical elements, grouping them into gases, metals, nonmetals, and earths. Chemists spent the following century searching for a more precise classification scheme. In 1829, Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner observed that many of the elements could be grouped into triads based on their chemical properties. Lithium, sodium, and potassium, for example, were grouped together in a triad as soft, reactive metals. Döbereiner also observed that, when arranged by atomic weight, the second member of each triad was roughly the average of the first and the third this became known as the Law of Triads. German chemist Leopold Gmelin worked with this system, and by 1843 he had identified ten triads, three groups of four, and one group of five. Jean-Baptiste Dumas published work in 1857 describing relationships between various groups of metals. Although various chemists were able to identify relationships between small groups of elements, they had yet to build one scheme that encompassed them all.

In 1857, German chemist August Kekulé observed that carbon often has four other atoms bonded to it. Methane, for example, has one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms.This concept eventually became known as valency; different elements bond with different numbers of atoms.

In 1862, Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois, a French geologist, published an early form of periodic table, which he called the telluric helix or screw. He was the first person to notice the periodicity of the elements. With the elements arranged in a spiral on a cylinder by order of increasing atomic weight, de Chancourtois showed that elements with similar properties seemed to occur at regular intervals. His chart included some ions and compounds in addition to elements. His paper also used geological rather than chemical terms and did not include a diagram; as a result, it received little attention until the work of Dmitri Mendeleev.

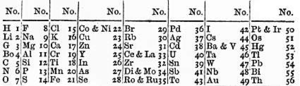

In 1864, Julius Lothar Meyer, a German chemist, published a table with 44 elements arranged by valency. The table showed that elements with similar properties often shared the same valencyConcurrently, William Odling (an English chemist) published an arrangement of 57 elements, ordered on the basis of their atomic weights. With some irregularities and gaps, he noticed what appeared to be a periodicity of atomic weights among the elements and that this accorded with “their usually received groupings”.Odling alluded to the idea of a periodic law but did not pursue it.He subsequently proposed (in 1870) a valence-based classification of the elements.

English chemist John Newlands produced a series of papers from 1863 to 1866 noting that when the elements were listed in order of increasing atomic weight, similar physical and chemical properties recurred at intervals of eight; he likened such periodicity to the octaves of music. This so termed Law of Octaves, however, was ridiculed by Newlands’ contemporaries, and the Chemical Society refused to publish his work. Newlands was nonetheless able to draft a table of the elements and used it to predict the existence of missing elements, such as germanium.The Chemical Society only acknowledged the significance of his discoveries five years after they credited Mendeleev.

In 1867, Gustavus Hinrichs, a Danish born academic chemist based in America, published a spiral periodic system based on atomic spectra and weights, and chemical similarities. His work was regarded as idiosyncratic, ostentatious and labyrinthine and this may have militated against its recognition and acceptance

Recent Comments